Some chains—and even online startups—have learned they risk losing business without a steady flow of weekly circulars to nudge shoppers.

One old-school retailing trick has survived the e-commerce shakeout—the lowly advertising circular.

Some grocers and other retail chains have learned they risk losing business without a steady flow of paper mailings nudging shoppers to stores. Even online startups that don’t have physical shops are embracing the idea.

Paper ads that arrive in homes spur more buying than emails or texts, said Jackson Jeyanayagam, chief marketing officer of Boxed.com, an online seller of household goods. “Email is starting to become a sandbox because you get so much,” Mr. Jeyanayagam said. Boxed spent 80% more on print advertising in 2017 compared with 2016 and says it now makes up about 12% of the marketing budget.

Most retailers still see digital advertising as a growing focus of their spending, and many continue to cut back on traditional print ads as well as mailers. But more are also experimenting with new ways to send out deals on paper, sometimes mining online behavior or databases of shopper trends to improve their direct mail.

PebblePost, a New York City marketer, uses online browsing and buying data from retailers and brands to send relevant coupons and ads to homes within a few days. For example, it might send a printed offer for free shipping if a shopper browsed a site without buying, said Lewis Gersh, chief executive of the firm.

At Jet.com, the e-commerce site that Wal-Mart Stores Inc. bought in 2016, direct mail makes up 10% of the media budget and is the online retailer’s largest offline marketing expense. Jet sent around 35 million paper coupons and mailers last year, which are effective in reaching new and repeat shoppers as the company tries to attract more urban, affluent shoppers, said Emily Frankel, senior director of digital marketing.

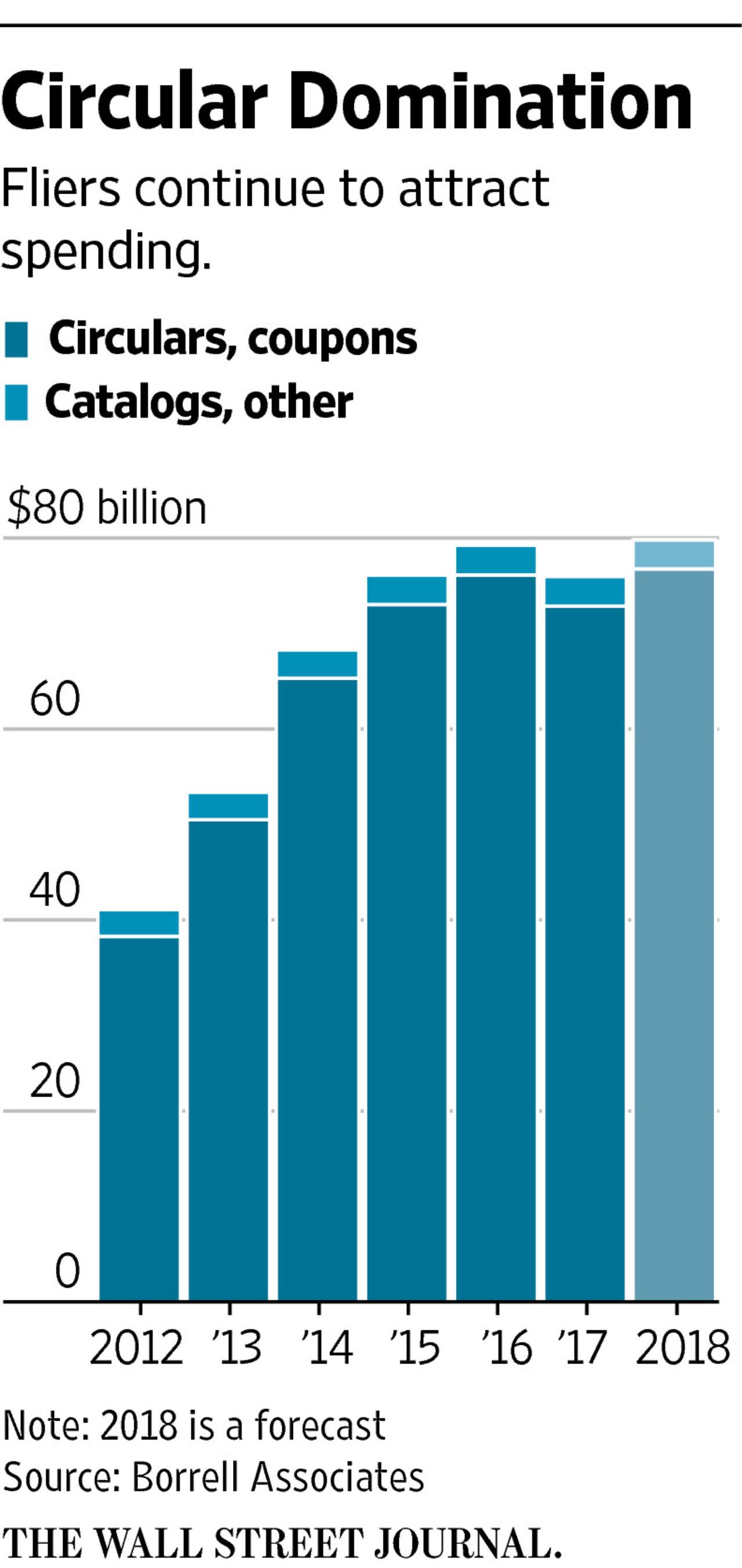

Annual spending on newspaper circulars, coupons, direct mail and catalogs hit about $76 billion in 2017, slightly lower than the previous year but up 85% versus 2012, according to Borrell Associates, a media consulting firm. The firm expects spending on some forms of mailed ads to fall as the U.S. Postal Service raises rates in coming years, said Kip Cassino, executive vice president at Borrell.

For now, paper fliers keep piling up on doorsteps because most people still read their mail, even as they easily ignore most online banner ads and many emails. Product manufacturers support the system by paying for coveted circular space. Retailers often ask suppliers to reduce prices of items they plan to feature in a mailer, or require a marketing fee—a source of revenue.

“Some get caught in a bit of a death spiral of promoting,” said Nick Goad, global lead for pricing and promotions at the Boston Consulting Group. Once retailers and their suppliers get hooked on sales boosts from circulars, it’s hard to stop. “It’s a little bit of a drug,” Mr. Goad said.

Early last year, visits to Costco Wholesale warehouse stores slowed slightly after the retailer sent fewer paper pamphlets touting deals. “We decided to change back immediately,” said Costco’s finance chief, Richard Galanti. Still, Costco made adjustments, offering deeper discounts on fewer products that it hopes will better drive sales, Mr. Galanti said.

Grocers usually pick which products go on the front of circulars based on a mix of past sales, deals with suppliers and gut instinct. That’s why meat dominates the cover during summer barbecue season, chips around the Super Bowl and candy before Halloween.

Now some chains are trying to make circulars more precise. “Smart retailers are marrying predictive analytics with circulars,” said Michael Osborne, Chief Executive of SmarterHQ, a digital marketing firm based in Indianapolis. Consumers buy more when they “receive promotions and discounts on items that they may actually be interested in.”

Harps Food, a Springdale, Ark.-based chain of 87 stores, last year started using Canadian data-analytics firm Daisy Intelligence to review which products should be featured in its frequent circulars, said David Ganoung, vice president of marketing at Harps. “Our print circular is our largest advertising expense and you want to be as efficient as you can.”

Harps has used the data from Daisy to expand the range of advertised products, often adding more produce, Mr. Ganoung said. The grocer also can measure how a circular deal influences what else a shopper might buy, he said. “So I put a hot price on Yoplait. Did I cannibalize from a regularly priced Chobani product that the shopper was already going to buy?”

Sarah Nassauer for Wall Street Journal